Inca Trail Road System

Written by Nate Aleshire

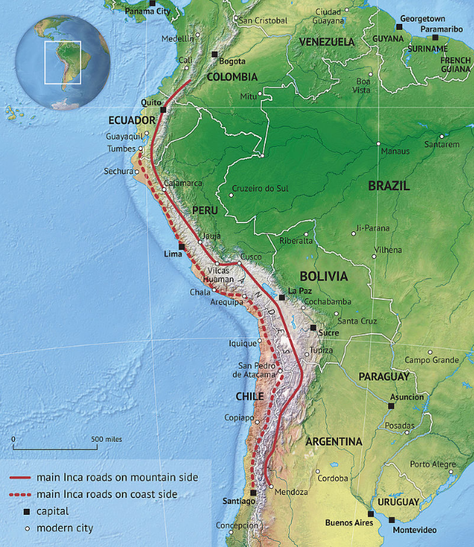

Few modern conveniences seem more basic than roads. While the Roman Empire’s road system has received moderate attention from historians, an often overlooked network of roads can be found in the Inca Empire. It was known as the Qhapaq Ñan, “the Road of the Inca.” Stretching across 24,000 miles and spanning throughout the modern countries of Ecuador, Peru, Colombia, Bolivia, Argentina, and Chile, these pathways allowed the Inca Empire to function efficiently. Perhaps the most impressive features located along these highways are the bridges, which are constructed to overcome the peaks of the Andes Mountains. An incredible span of Inca roads still exists today, and the network is a World Heritage Site listed with UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization).

Like the road system of the Roman Empire, the Incas used their highways for the transportation of soldiers and materials, enabling a flourishing economy through trade and a powerful, mobile military. Inca highways also enabled relatively quick means of communication, as runners were stationed periodically along the sections of road. The most significant sections of the road ran from north to south, reaching from Peru through Argentina, and east to west through Ecuador and Argentina. Each section was measured in the Inca topo, a distance that is roughly equal to 4.34 miles. Inca engineers were ambitious, carving pathways through sheer cliff sides and crossing biomes ranging from jungles to mountains to deserts. They also had to overcome geographical features like rivers, valleys, and ravines. Additionally, the Inca builders incorporated pre-existing passages, and learned from those examples. The Tiwanaku, Wari, and Chimu peoples are a few of those emulated and improved upon by the Incan. Even more impressive was that each part of it was designed and built without either iron or wheeled tools.

Like the road system of the Roman Empire, the Incas used their highways for the transportation of soldiers and materials, enabling a flourishing economy through trade and a powerful, mobile military. Inca highways also enabled relatively quick means of communication, as runners were stationed periodically along the sections of road. The most significant sections of the road ran from north to south, reaching from Peru through Argentina, and east to west through Ecuador and Argentina. Each section was measured in the Inca topo, a distance that is roughly equal to 4.34 miles. Inca engineers were ambitious, carving pathways through sheer cliff sides and crossing biomes ranging from jungles to mountains to deserts. They also had to overcome geographical features like rivers, valleys, and ravines. Additionally, the Inca builders incorporated pre-existing passages, and learned from those examples. The Tiwanaku, Wari, and Chimu peoples are a few of those emulated and improved upon by the Incan. Even more impressive was that each part of it was designed and built without either iron or wheeled tools.

Inca engineers and construction workers would have had tools made from wood, stone, and bronze. The roads themselves would have mostly been packed with dirt, gravel, or sand if the local geography made it easier to access. These were usually raised above the surrounding ground, so the culverts and drains allowed for drainage on and near the roads. Road widths varied, but were typically between 3 and 12 feet. However, more densely populated urban areas would have needed roads that were much wider and much more sturdy. Urban or heavily-traveled highways would have been made from stones, carefully arranged and supported, with drainage systems similar to those found in more rural sections of the road network. Furthermore, the widest known road was 45 feet wide. While the road was certainly usable throughout the empire, it was also not uniform in its construction, styles, or materials used. This is because different groups of people were used as workers, and there was no certain code for the road system. More complicated structures, like short bridges, were usually made from reeds or stone. Stairs carved into the mountain sides were for use by the people of the empire, as well as llamas, the only pack animal (an animal used to carry heavy loads) by the Inca. However, the most impressive aspect of the road system would have been the rope suspension bridges. Stretching across ravines, the longest of these marvels of pre-ironworking engineering was more than 130 feet long. They were made with braided ropes of reeds or grass. If bridges were not feasible, greater distances could be crossed using an oroya. This was a basket attached to a rope, not unlike modern tramways, cable cars, or ski lifts, though much smaller.

The Inca road network was constructed with chaotic and destructive weather in-mind. Over half a millennium, many have survived floods and torrential downpours brought on by El Niño, a weather pattern that occurs every few years. Inca engineers took these weather events into consideration, as well as seismic activity and more regular seasonal patterns. They chose routes through terrain and the materials used to construct infrastructure accordingly. Furthermore, there was a spiritual significance to the Inca roads, as well as a psychological one, as all roads led to the Inca capital, Cusco.

The Inca road network was constructed with chaotic and destructive weather in-mind. Over half a millennium, many have survived floods and torrential downpours brought on by El Niño, a weather pattern that occurs every few years. Inca engineers took these weather events into consideration, as well as seismic activity and more regular seasonal patterns. They chose routes through terrain and the materials used to construct infrastructure accordingly. Furthermore, there was a spiritual significance to the Inca roads, as well as a psychological one, as all roads led to the Inca capital, Cusco.

The efficiency of Inca road systems could easily be attributed to extensive state-control within the empire at large. The government maintained and regulated the highway network, noting the movements of people and trade goods, while also closely monitoring the status of pathways, bridges, stairways, and other features of the roads. This thorough record keeping would have been a necessity to hold the empire together. The Inca Empire was known as Tawantinsuyu, “the four regions together.” As evidenced by the name, the empire only came into regional power as factions were either united or conquered, and this occurred in a rapid period of time, only about 100 years. This would have meant that different groups may not have been accustomed to working so closely together. They may have required the oversight of the Inca state to remain in relative peace. Inca roads were not available for private use by commoners unless given explicit state permission, giving the government a system for monitoring and taxing trade. Not only for military, economic, or governmental use, the Inca road network also allowed upper class members of society to venture to retreats like Machu Picchu.

However, the benefits of a well-maintained and extensive road system were not exclusively relegated to the Incas. When the Spanish arrived in 1532 and began waging war to conquer the empire, they were able to utilize the Inca roads to quickly move between cities and strategic points. By that time though, the Inca Empire had already been dealt a fatal blow. A civil war had weakened the state prior to and during the Spanish invasion, and outbreaks of the deadly and infectious disease of smallpox preceded the Europeans. As the disease traveled quickly along trade routes and between messengers and refugees, the empire was primed for invasion. When Spaniards took Cusco, they made Lima the colonial capital, lessening the importance of connections forged throughout that area. Furthermore, the Europeans were more concerned with stripping raw materials from the area than maintaining Inca roads that did little to further their ends. Many roads went underused and fell into disrepair, as connections between communities eroded away.

However, the benefits of a well-maintained and extensive road system were not exclusively relegated to the Incas. When the Spanish arrived in 1532 and began waging war to conquer the empire, they were able to utilize the Inca roads to quickly move between cities and strategic points. By that time though, the Inca Empire had already been dealt a fatal blow. A civil war had weakened the state prior to and during the Spanish invasion, and outbreaks of the deadly and infectious disease of smallpox preceded the Europeans. As the disease traveled quickly along trade routes and between messengers and refugees, the empire was primed for invasion. When Spaniards took Cusco, they made Lima the colonial capital, lessening the importance of connections forged throughout that area. Furthermore, the Europeans were more concerned with stripping raw materials from the area than maintaining Inca roads that did little to further their ends. Many roads went underused and fell into disrepair, as connections between communities eroded away.